New evidence in the scientific community indicates that there is a strong correlation between COVID-19, its related vaccines, and the reactivation of other viruses which have previously infected the host. This article will dive deeper into the nuances.

In the number of years I spent in the military as a microbiologist, I’ve always been quite impressed with how shrewd viruses can get. During viral infections, viruses have to deal with the defense of the immune systems. If the immune system has the upper hand and defeats the viruses, viruses might develop mechanisms to stay dormant and become inactivated.

One such mechanism is to insert their viral DNA into cells’ chromosomes, staying in latency without active replication. Other mechanisms might involve promoting epigenetic silencing of the viral genome, meaning they stay “muted” in activity, but present and lying in wait.

Host cells will then reproduce cells still carrying the viral genetic information. Then, viruses might come back years, or even decades later, reactivating the viral replication when the immune system degrades. This prudent strategy where viruses turn into a latent enemy within the host is quite an effective strategy against the enemy, whether in the military or the human body.

The scientific community is very familiar with five types of viruses that are able to “hibernate” and reactivate given suitable conditions:

· Herpes simplex virus, which causes blisters in the mouth and genital herpes. It is extremely common;

· Varicella zoster virus (VZV), more commonly known as chickenpox;

· Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), which causes mononucleosis or “mono,” the “kissing disease,” as it can be transmitted when people kiss each other;

· Cytomegalovirus (CMV), which usually causes a great deal of trouble for immunocompromised people but not really otherwise;

· Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), which causes AIDS; this virus can stay in your body for more than a decade before becoming activated.

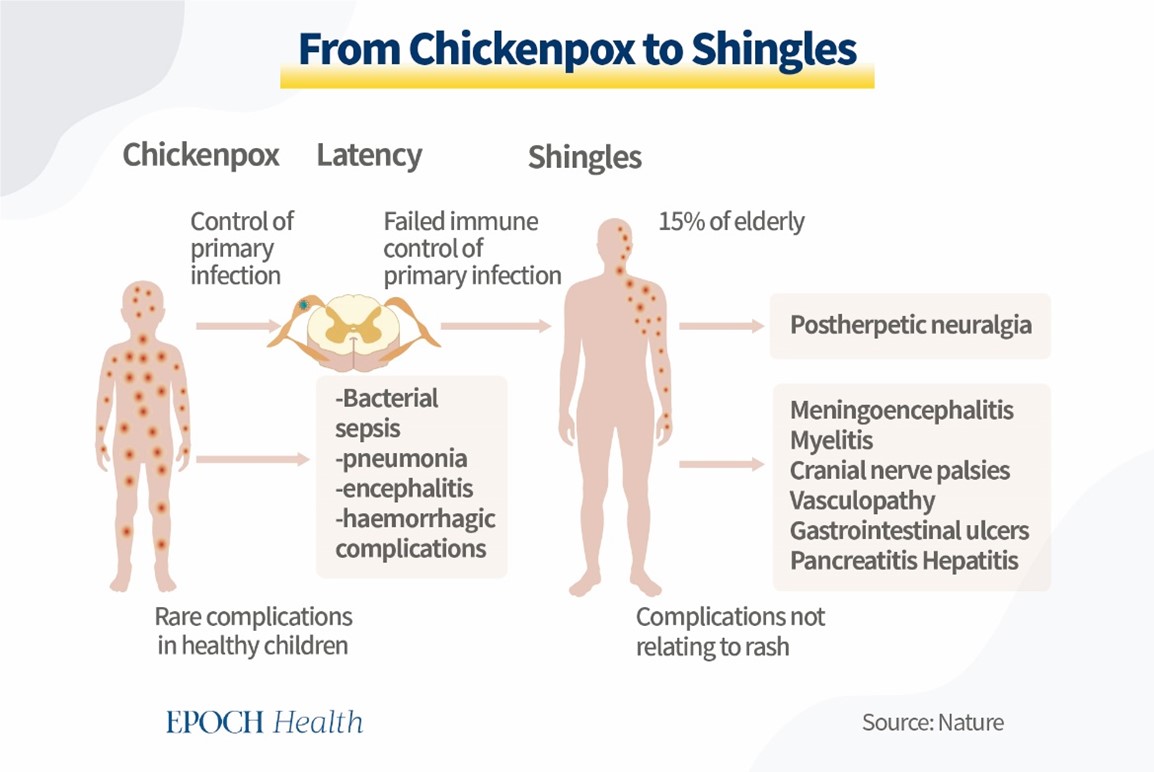

Let’s take VZV, or chickenpox, as an example. In the usual sense, everybody gets chickenpox in their life. This usually happens early on and is quite itchy for the patient but doesn’t have a lot of other severe complications.

After the patient initially overcomes VZV, it never truly goes away. It has the possibility of coming back, especially with the weakening of the immune system. It can attack again in a more severe form called shingles or Herpes Zoster. Shingles is a very painful rash that develops on one side of the body. In some cases, it may also cause chronic nerve pain or other serious complications, including blindness. Shingles can also be caused by advanced age, stress, diseases (chronic or acute), cancer, or various other sources. In fact, the aforementioned factors usually also lead to the reactivation of other viruses. Chronic fatigue might lead to reactivating EBV, herpes might be reawoken with surgery, and HIV might be kickstarted by tumors.

A popular theory behind why viruses can be reactivated is that, after the initial wave of viruses was defeated, the body has a large fleet of naive CD-8 T-killer cells (immune cells that get rid of pathogens they don’t recognize) which serve to keep the remaining number of viruses in check. When the immune system is placed under a lot of stress, such as during acute infection, when battling cancer, or after an organ transplant (due to the administered immunosuppressant drugs), those naive CD-8 cells go down in number one way or another. The virus then seizes the chance to proliferate when defenses are down.

Although it is unclear what exactly lets the viruses know that the immune system is compromised or otherwise occupied, there is now an increasing pool of data that strongly correlates the reactivation of previous viruses and a COVID-19 infection or even vaccination.

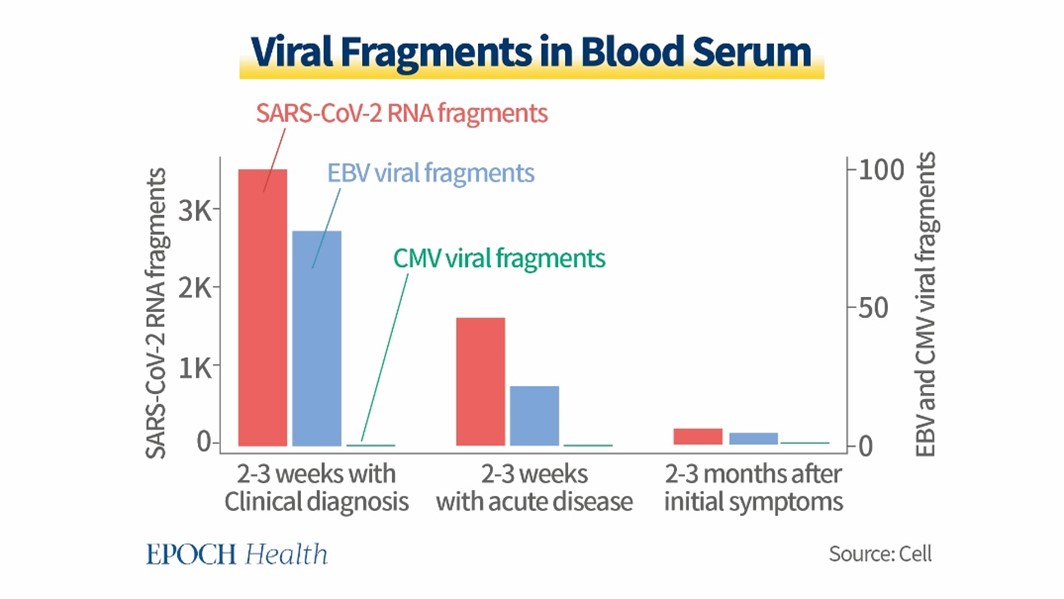

For example, in the journal Cell, scientists published a study that followed around 300 COVID-19 patients and tested their blood serum for viral fragments including from the Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV), the Cytomegalovirus (CMV), as well as SARS-CoV-2 itself.

The researchers recorded fragment levels two to three weeks after clinical diagnosis of COVID-19, two to three weeks after acute disease onset, and two to three months after initial symptoms. The researchers found that although viral fragment levels of other diseases were never higher than that of SARS-CoV-2, EBV fragment levels were still quite high. Then, is this due to coinfection of COVID and EBV, or reactivation of latent EBV after COVID infection?

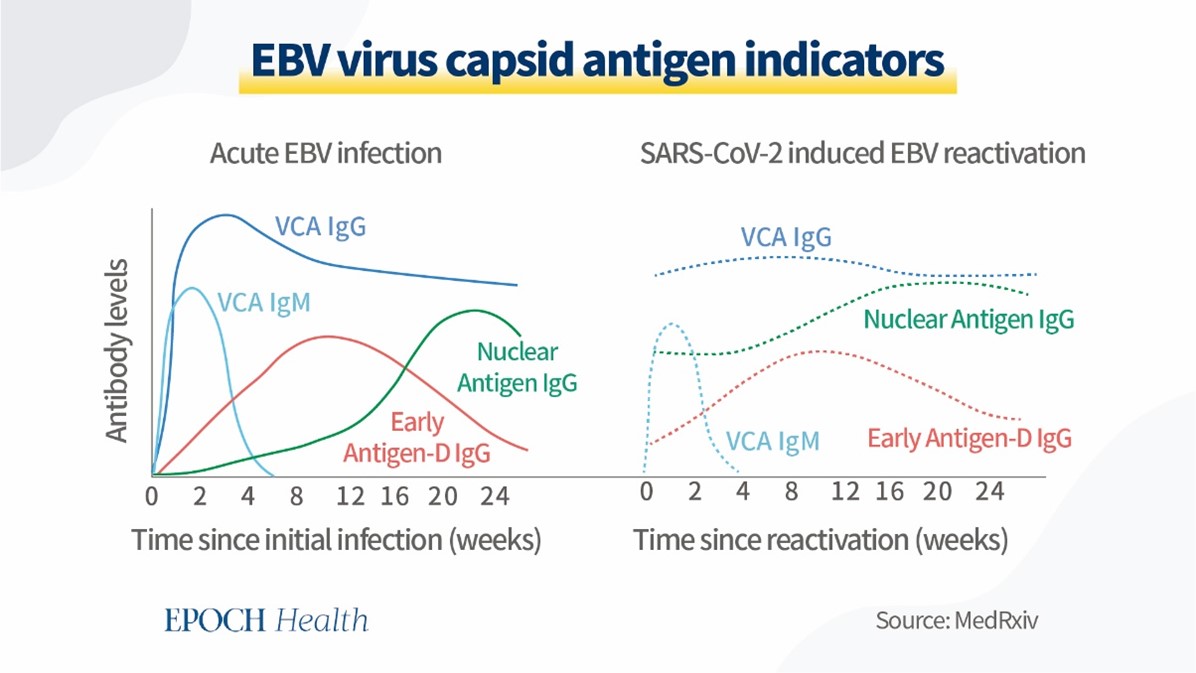

Actually, studies have found that the fluctuation patterns of antiviral IgG levels can indicate whether this is coinfection or reactivation of latent EBV. In the diagram illustrated here, the solid lines represent antigen levels for EBV during acute infection, and the dashed lines are predicted antigen levels for a reactivation of EBV caused by SARS-CoV-2.

So, there are two major differences: one is that IgG antibody levels against viral capsid protein (VCA IgG) will be low during the initial one to two days of infection, while VCA IgG will start from a high level if it is a reactivation case. The second difference is that the IgG against nuclear antigen (NA protein) will have a slow curve to increase its level if it is related to acute EBV infection on top of COVID, but the NA IgG will start from medium to high level if it is a reactivation of latent EBV.

COVID-19 sometimes leads to an infamous syndrome called long covid, also known as post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC). Long covid patients often experience “unremitting fatigue, post-exertional malaise, and a variety of cognitive and autonomic dysfunctions” for a prolonged period of time.

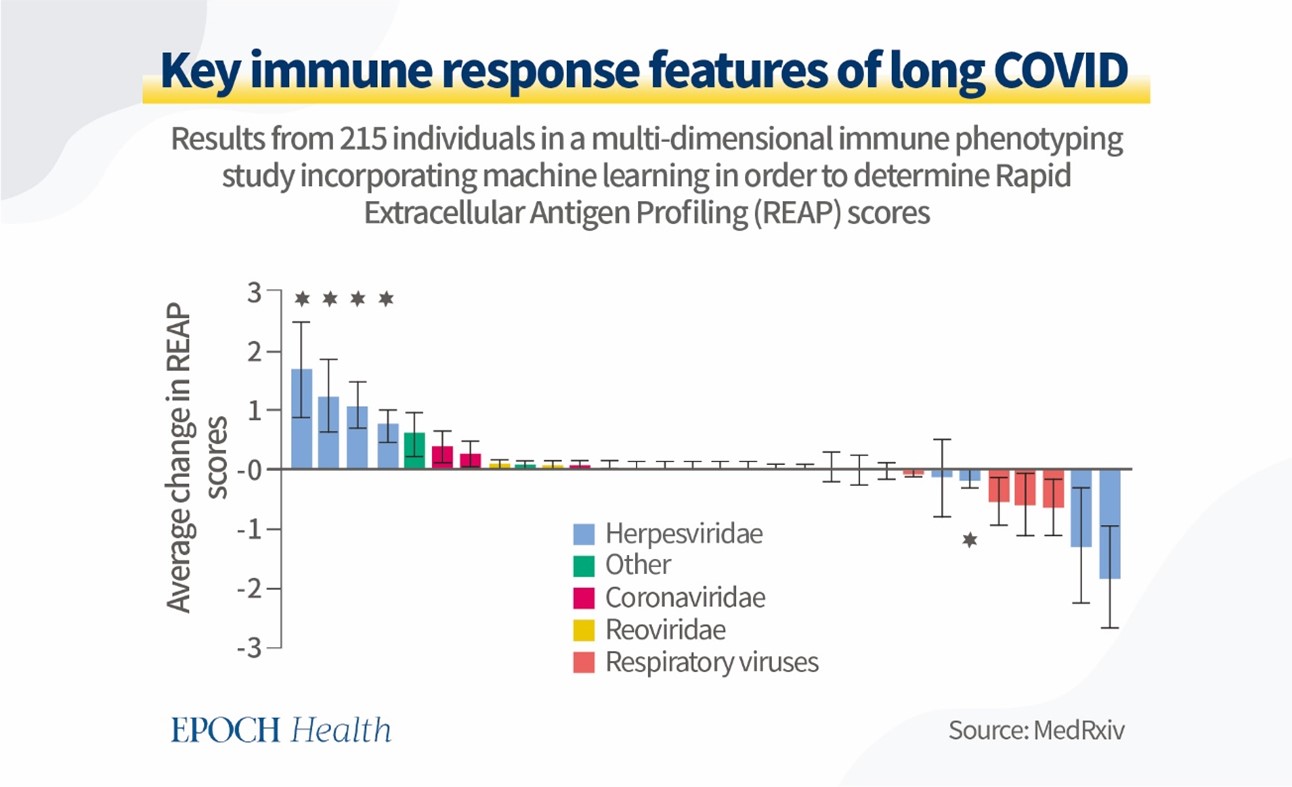

This means that the immune system is under a terrific amount of stress struggling with these symptoms, which some scientists speculated to be quite the precursor to the reactivation of various hibernating viruses. In a cross-sectional study, 215 participants were analyzed for key features that distinguished long COVID.

The results were surprising in the sense that many antibody responses were raised against not only SARS-CoV-2, but also other viruses such as EBV and VZV. Using a process called rapid extracellular antigen profiling (or REAP), scientists were able to identify an elevated REAP score for many viruses belonging to the family herpesviridae, indicating that these viruses were reactivated during a COVID-19 infection.

Long COVID is known to cause a lot of issues even disregarding the reactivation of previous viruses, but what about the COVID-19 vaccines? Will they cause something similar?

COVID-19 vaccines simulate the COVID-19 infection in a special way and force the immune system to adaptively react to it. During the time when the immune system is processing the vaccine, it effectively redirects the attention of a lot of the naïve CD-8 T-killer cells to the COVID-19 spike proteins, and might leave a fleeting moment for some viruses from past infections to resurface.

The Epstein-Barr virus (EBV or mono) is ubiquitous in the global population and usually doesn’t cause a lot of trouble. Only in patients with severe immune deficiencies, such as after an organ transplant, will EBV lead to severe or even fatal complications.

One study looked at patients with an organ transplant history and analyzed their EBV fragment levels before and after receiving a full course of COVID-19 vaccination. They found that EBV levels in this category of patients were significantly higher after vaccination.

Another case study related to EBV analyzed its reactivation in a young and healthy man after he was administered a COVID-19 vaccine. This was the first case of EBV reactivation in a healthy, immunocompetent adult post-COVID-19 vaccination. These incidences indicate a strong correlation between the vaccine and dormant virus reactivation.

According to the REAP data above, shingles or herpes zoster (HZ) was another virus that correlates to COVID-19 in terms of reactivation. An Indian case study analyzed 10 cases of shingles directly after the COVID-19 vaccine, where the onset of symptoms occurred within 21 days post-vaccination. In the study, 80 percent of the patients in the study didn’t have any other factors which might have led to the reactivation. Two patients, who had diabetes as the only other possible factor, already had it well under control before the vaccination. This is not the only case report in relation to shingles.

An article published in The Lancet reveals that 16 and 27 cases of shingles were discovered after the administration of CoronaVac (Sinopharm) and BNT162b2 (Pfizer/BioNTech) vaccines when analyzing vaccination records from the Hong Kong Department of Health. The study concluded that shingles would likely occur in about seven or eight in 1 million doses administered. A more systematic case report which summarized 91 cases of post-vaccine HZ found that the mean symptom onset time was just under six days, with hypertension as the most common comorbidity and autoimmune conditions being fairly prevalent among the patients.

Data from the WHO global safety database shows that there are already over 7000 cases of HZ found worldwide, meaning that this is not an isolated issue. By May 2022, the United States Vaccine Adverse Event Report System (VAERS) has already reported 4,577 cases of HZ post-vaccination, and the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MRHA) of Great Britain reported 2,527 HZ cases. It is important to note that HZ is likely an underreported occurrence as a post-vaccination complication.

Other viruses mentioned in the beginning, such as the Cytomegalovirus (CMV) and the cancer-inducing Kaposi’s Sarcoma-associated Herpesvirus (KSHV) have also seen case reports or studies that document their reactivation after the administration of anti-COVID-19 drugs. Scientists are even discussing whether SARS-CoV-2 itself can embed itself in humans only to become reactivated in the unforeseeable future, but it is generally too early to tell.

The hotly contested issue at hand is how we should treat the issue of vaccination for those at risk of having their old diseases “rise from the dead” or “wake up from hibernation.” The discussion of antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE), which raises the risk of booster vaccines causing more severe illness than otherwise, begs the question of whether vaccines effectively lead to easier infections, whether COVID or old viruses and diseases.

It is important to note that the studies validate the correlation between the COVID-19 infection or vaccine and the reactivation of various viruses from their dormant period, but it is in no way meant to indicate causation. However, there needs to be a well-calibrated balance between administering vaccines to individu

The official guidelines are to get the elderly vaccinated first in order to protect them from strong ramifications as a result of a COVID-19 infection. It is true that most coronavirus deaths are from that age group and that the elderly suffer the most under this virus.

However, we have to keep in mind that, empirically, this age group is precisely the group at high risk of having other viruses reactivated when their immune system has a burden to face.

This is why a delicate balance of risks and benefits must be maintained when operating under the assumption and guise of prevention and protection.

Any opinions, views and beliefs represented in this article are personal and belong solely to the author/s and do not necessarily reflect the opinion, views and beliefs of the organisation and employees of New Image™ International